Bernie Sanders’s online supporters are a tremendous campaign asset. Their extraordinary numbers and hyper-connectedness have helped power a jaw-dropping fundraising behemoth. Their passion is a reminder that Sanders might be the only candidate with a real base in the race. And their ubiquity on social media serves as a counterweight to the bourgeois press’s open war against the promise of social democracy.

But some of them are also a liability.

The infamous Bernie Bro archetype that originated during the 2016 primaries is once again rearing its head — and there are many signs that an ascendant leftist movement is underestimating how much damage it could do to their cause.

Back in 2016, the context and the meaning of the term were different. There were two premises to the charge: (1) Sanders’s support was disproportionately white and male and (2) These white men were rude and aggressive and were typically inattentive to the experiences of racial minorities and other marginalized groups.

There was some truth to the first claim. During that primary season Sanders’ supporter base skewed white and male. The second claim I didn’t find convincing, and seemed overly reliant on a handful of reporters’ anecdotal sketches.

Overall, the charge of Bernie Bro was a crude weapon employed by some Hillary Clinton supporters. It failed to take into account how there was real diversity in the core of Sanders’ base: young people. And what vexed me most was that it effaced the many nonwhite and women lefties — both online and offline — who made a compelling case for Sanders based precisely on antiracist and feminist critiques.

This time around, the Bernie Bro charge is different. It’s widely known that Sanders supporters are extremely diverse in terms of gender and race and class, and the notion that only those “privileged” can afford to adopt a more radical worldview has been revealed to be absurd, as it always was. The second prong of the archetype has manifested again, though, but in a different form. Now the claim is that Sanders supporters online are disproportionately likely to be cruel and obnoxious, or bully and harass people.

Unfortunately I think this claim has some legitimacy. And I think that the many Sanders supporters online who are going to lengths to rationalize or defend the adversarial style are too plugged in to the incentives of social media popularity contests and out of touch with what it will take to win an election and build a sustainable leftist movement.

Hostility as a political culture

Every candidate in the race has some belligerent supporters who sometimes go too far in online debate. But there is an easily discernible culture of disdain for opponents and rivals among a very vocal set of Sanders supporters online.

It’s difficult to measure the size of this group, but it’s safe to say it constitutes a small minority of Sanders’s following online, and a far smaller fraction of Sanders’ total base of supporters around the nation. It’s also safe to say that this network is very prominent in responding to competitor candidates’ announcements/ads, prominent criticism of Sanders, news reportage on the 2020 race, and just general political debate between members of the press, activists, candidate supporters, and Democratic party elites on social media.

This culture of disdain finds expression in things like the circulation of memes likening Pete Buttigieg to a rat and swarming Elizabeth Warren’s Twitter and Instagram accounts with snake emojis with the intention of, well, calling her a snake. This group of Sanders supporters has a taste for verbal combat and denigration, and openly expresses disgust, abject mistrust, death wishes, sadism, imperiousness, and profanity toward people they disagree with, even — and sometimes especially — progressive press, politicians, and activists. They thrill in “ratioing” Sanders critics, or basically dog-piling on someone for saying something they perceive as inaccurate, stupid, or offensive with put-downs and barbed denunciations.

Beyond the adversarial style, there’s also the issue of bullying and harassment. According to the New York Times, there are numerous examples of Sanders supporters taking things to the level of abuse: several feminist writers have reported death threats; some progressive activists have traveled with private security after online harassment; a state party chairwoman was forced to change her phone number after receiving threats against her family; a lawyer saw their business ratings targeted by Sanders supporters after an online interaction went sour. Recently they doxed a Daily Beast reporter for publishing a Sanders campaign staffer’s private tweets disparaging other candidates based on their appearance and sexuality on a private Twitter account.

The Nevada Culinary Union debacle has taken on a particularly high profile. After the union took aim at Sanders over his health care policy the night of the New Hampshire primary, some Sanders supporters allegedly reacted with a harassment campaign. Per the Nevada Independent:

Two top Culinary Union officials have faced threatening phone calls, emails and tweets and say their personal information was shared online after the release of a union scorecard that took particular aim at Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders. Secretary-Treasurer Geoconda Arguello-Kline, for instance, has come under attack for her Nicaraguan heritage, and union spokeswoman Bethany Khan was accused of being paid off by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and other Democratic establishment types. In tweets, the union and its leadership have been referred to as “bitches,” “whore,” “fucking scab” and “evil, entitled assholes.”

This specific incident is tricky to assess. It’s difficult to verify the identity or political agenda of the culprits. Given that it does seem to be categorically worse than most of what we’ve seen so far, it does seem slightly more likely than in other situations that covert campaigns meant to smear Sanders or divide the electorate could be at play. There’s also just downright weird chaos online — the Nevada Independent found, for example, that one person disparaging the union with racist language was … a Trump supporter who opposes Medicare-for-all. Sanders has condemned the attacks several times, and also pointed out that foreign interference is a possibility.

But even if we determine that it was an outlier incident, and that it cannot not be firmly attributed to the bellicose online camp among Sanders’s followers, it’s worth considering why it seems, in the eyes of many, including myself, plausible. Given what I’ve observed in leftist spaces online for years, it seems possible that at least some genuine Sanders supporters might have contributed to at least some of those repugnant Nevada attacks. Why? Because some of them believe ideologically that nastiness is the way to win.

The politics of vulgarity

For me, a lot of it stems from the fact that the culture of disdain among some Sanders supporters is a part of a self-conscious political style.

Consider, for example, Chapo Trap House’s corner of the Berniesphere. Chapo Trap House, a left-wing political comedy podcast with hundreds of thousands of devoted listeners and followers online, actively cultivates the attitude that calls for civility in discourse are not only lame, but also often act as a shield for morally bankrupt status quo politics. In the eyes of this scene, which is sometimes referred to as the Dirtbag Left, rejecting civility is a tactic.

Amber A’Lee Frost, a member of Chapo Trap House, wrote a stylish essay on this issue for Current Affairs in 2016 entitled, “The Necessity of Political Vulgarity,” in which she defines vulgarity thusly:

[Vulgarity is] the crass, ugly dispensation of judgment with little to no regard for propriety. Vulgarity is the rejection of the norms of civilized discourse; to be vulgar is to flout the set of implicit conventions that create our social decorum. The vulgar person uses swears and shouts where reasoned discourse is called for.

In this essay, she argues that “rudeness can be extremely politically useful” by elucidating how vulgarity can tarnish the prestige of elites and caricaturing an opponent can be “illuminating even at its most indelicate.” The one example she provides to demonstrate this point is the argument by some historians that crude, pornographic caricatures of the French monarchy corroded their authority in the run-up to the French Revolution, and may have made the execution of Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette more likely.

Chapo’s podcasts employ this ethos of political vulgarity to great effect. I’ve listened to about half a dozen episodes of the show, and its takedowns of mainstream liberal institutions are funny and insightful.

But political vulgarity takes on a different meaning as a model of activism, which is something it has become as Chapo and its crowd have grown into zealous Sanders activists online. Takedowns, profane dismissiveness, and vilification of opponents are no longer an in-group ritual during which a consistent set of listeners or somewhat self-contained Twitter scene blow off steam, but are instead deployed outward as a weapon. Polemicism has gone from a mode of analysis to a mode of actual engagement with citizens online in skirmishes over the primary.

Additionally, a superciliousness seems to have taken hold in the Dirtbag Left scene as Sanders has performed strongly in the primaries and some people on the left have become intoxicated by the prospect of Sanders winning the presidency. For example, before the Iowa caucuses Chapo host Will Menaker said in a note of encouragement to his followers, “If all goes as planned on Monday, you will never have to take seriously or even pretend to respect any of these awful, hateful morons ever again. Keep it up, we’re almost there.” In the run-up to the New Hampshire primary, Menaker tweeted: “The two paths laid out for the liberal media if Sanders wins on Tuesday are already being prepped: the Yglesias knee bend, ‘he’s just like me or any other regular Democrat and won’t be so bad’ and the Chris Matthews full red-bait meltdown. This is very, very good.” There’s also been talk of forming a potentially boycotting voting bloc to apply additional pressure. Amidst the disastrous Iowa vote count, Menaker tweeted that he wouldn’t vote for anyone but Sanders in the general election.

I do not think that Chapo is the main or only source of this set of attitudes online. (I also have not seen them engage in what I would consider harassment campaigns.) But they typify some of the adversarial style I’ve seen across many spaces where hard leftists congregate or swarm, and it seems they’ve helped either coin or popularize some of its vocabulary and values.

I recommend reading this exchange I had with a leftie who followed me (but no longer does, it seems) whose bio said they were “Commisar in the Chapo Internet Armed Forces.” After I recently questioned the utility of him calling Warren a snake in my mentions he told me that Warren supporters “must bend the knee or pull their masks off and join their fellow reactionaries” and that they are “not needed to construct a working class political coalition.”

“They are mostly upper middle class professionals who have a shallow understanding of politics,” he added.

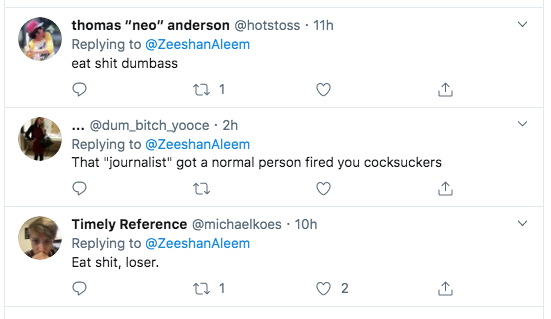

One might think that because I write from a left perspective that I might not have had belligerent Bernie energy directed at me. That is not the case. For example, when I tweeted on Monday that it was ironic that a journalist who reported on inappropriate language in a Sanders’s staffer’s social media posts was being harassed with inappropriate language, I myself received some flak of the politically vulgar variety. Behold:

I did not care about this. As a journalist, I have fairly thick skin when it comes to dealing with insults, attacks or unpleasant language from strangers online, and this was obviously mild. (It’s rather rare that I don’t receive racist emails or derogatory remarks after reading a widely-read piece.) But I can tell you this: this whole political style is profoundly dangerous for the left.

The perils of being a prick

My arguments for why this is a serious concern are not predicated on some fetish for civility. Vulgar modes of discourse against concentrated power and authoritarian figures do, as Frost discussed in her essay, have their place. I particularly value it as a form of comedy. But the idea of having this attitude permeate a burgeoning political culture and constantly inform the way one interacts in an activist setting with ordinary citizens, many of whom you will either need or want in your political coalition, is a big fucking problem.

Politics always involved persuasion

The Sanders supporter who delights in making Buttigieg rat memes, heaping scorn on Warren followers and demanding that squishy liberals “bend the knee” believes that they are a) boosting morale for their fellow Sanders supporters online and organizing on the ground and b) deflating the confidence of anyone getting in Sanders’s way. They are going all in on turnout: winning by mobilizing die-hard Sandernistas and disaffected and first-time voters.

This is short-sighted, to put it politely. First there is the issue that it may not succeed on its own terms. While Sanders is able to draw crowds like a rock star, his ability to drive people to the polls hasn’t proven exceptional so far:

- In Iowa, overall turnout was just 3 percent higher than in 2016, and the increase was chiefly in more highly-educated areas of the state — precisely where Sanders didn’t perform as well.

- In New Hampshire, turnout surged more in townships where Buttigieg and Klobuchar won than in townships where he won.

- In Iowa, Sanders beat Buttigieg among first-time caucus-goers by only 6 percentage points, and in New Hampshire he won them by just 4 percentage points.

- In Nevada, turnout was above 2016 levels, but below 2008 levels.

- Sanders absolutely dominated among Latinos in Nevada, but notably they constituted a smaller share of voters than in 2016.

- Overall, the proportion of first-time voters in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada shrunk compared to 2016 levels.

- There wasn’t a discernible surge in youth turnout across all three states.

This should be worrying to anyone who is certain that Sanders can win the nomination decisively by only mobilizing his base and pulling unlikely voters into the mix. Could it work? Yes. But it’s risky. As of this writing, FiveThirtyEight puts the odds that nobody wins a majority of delegates at 1 in 2, and the odds that Sanders wins a majority of delegates at about 1 in 3. While Sanders is plainly the frontrunner in this race, it’s far from clear that his margin will be decisive enough to guarantee him the nomination.

All this is to say: the Sanders campaign would be well-served by broadening its base.

The simplest way to increase the odds of winning a majority of delegates throughout the race would of course be to court Warren voters, a plurality of whom support Sanders as a second option due to their ideological kinship. Data indicates that Sanders is the second choice of plenty Biden supporters and even a non-trivial amount of Buttigieg and Bloomberg supporters. (Remember most voters are not ideologically coherent and Sanders has the highest favorability ratings out of any candidate in the race.)

But here’s where the ruthless turnout ethos shows its limitations and costs. Those snake emojis and tasteless jokes about Warren being Native American and accusations that she and her followers are all faux radicals don’t do Sanders any favors here. In fact, they’re probably going to convince some Warren voters to stick with her slightly longer, or maybe even reconsider ever switching to Sanders despite his strong standing in the polls. The Biden and Buttigieg backers who are convinced that Sanders supporters have formed a belligerent cult might hold back on Sanders when they might’ve otherwise considered switching to him after Bloomberg blows up the moderate lane.

One common excuse for shitty behavior I hear is that the Internet “isn’t real life.” I don’t find that persuasive. It’s 2020: the line between life online and offline is blurry and porous; a lot of people spend more time talking through screens than in-person; and online behavior isn’t considered unrepresentative of groups the way it used to be. Sure a fairly small percentage of Americans are “extremely online,” but it’s disproportionately made up of tastemakers, journalists, connected activists and political elites who have huge influence over the primary process — and primary voters follow their cues. More to the point, the whole reason this activist mode has emerged is precisely because its proponents believe that it affects people. Months and months of public debate and complaints about a set of over-the-top Sanders’s supporters is evidence that people feel it.

If Sanders ends up short of a majority of delegates before the DNC this summer, his and his following’s reputation for open-mindedness and ability to craft coalitions will be essential to winning over a delegate majority. As superdelegates conspire to deny Sanders the nomination, all those calls for insufficiently left progressives to bend the knee could very likely feel like a curse in that scenario. As Sanders makes pleas to delegates from other candidates to come to his side, could the culture surrounding some of his following make that task harder? I would surmise that it would.

Even if Sanders wins the nomination, there are other scenarios to be concerned about. The culture of disdain for outsiders could still take its toll in the general election, because turnout operations will require not just Sanders true believers but the entire Democratic electorate and the party’s campaigning infrastructure to win. It could hurt fundraising, it could mean a smaller percentage of progressive organizers join get-out-the-vote operations, it could mean more reluctant phone bankers, it could depress overall turnout. All these things make it harder to win the White House, the House and the Senate.

I’m not saying Bernie Bros will single-handedly torpedo Sanders’s campaign, but their defenders don’t seem interested in reckoning with the costs of alienating allies and dampening enthusiasm in an acutely competitive series of contests. Even just as a trope about the Sanders campaign they have the potential to continually sap him of some of his support. The benefits they offer for base turnout meanwhile, are highly questionable.

And unless anyone has forgotten: while we’re still learning how good Sanders is at pushing turnout, we know for a fact that Trump is a turnout machine.

The left should be collaborative if it wants to thrive

I’ve discussed how I doubt the efficacy of winning by degrading others. But there’s also the question of whether this is a cultural outlook that’s at odds with what the left stands for.

Before I get into this, let me just add a quick point about what it means to be “mean” online. Defining impropriety online is difficult. I think it would be difficult for people to achieve a consensus on what constitutes assertiveness vs. haughty mockery vs. aggressiveness vs. cruelty vs. bullying vs. harassment vs. abuse. It’s a complex issue, and I do not think these things should be conflated. And it should be clear that I’m critiquing this spectrum of behavior as a model of activist engagement, not making a blanket statement on how individuals conduct themselves in every situation.

In conversations about this issue with leftists, I have heard the argument on many occasions that it’s appropriate to use venom to convey outrage and a sense of urgency in the face of moral atrocities like the state of US healthcare or the specter of ecological catastrophe. This makes sense to me on an explanatory level, but I find it hard to use it as an argument for how the left should engage with the world.

One reason for this is that Sanders’s supporters do not have a monopoly on feeling desperate about the election or in their thirst for change. People across the political spectrum feel disenfranchised and alienated, but channel their political energy differently and settle on different candidates. Setting aside Bloomberg’s depraved subversion of democracy, this primary has been filled with a lot of well-intentioned candidates who really do want to improve society, and have proposed serious progressive ideas intended to do so. I happen to think many of Sanders’s ideas are the best ones out there, but leftists would be wise to remember that even the centrist candidates Biden and Buttigieg have proposed policy agendas that are dramatically more progressive than anything a Democratic nominee has run on in a general in decades — and that many of their followers genuinely think those are the best paths to doing things like fixing our health care disaster.

Understanding the subjectivity of other ideological camps and finding common ground is the only way the left can engage in the persuasion needed to build a sustainable movement. Searching for class traitors and mocking anyone who’s not in the know is inimical to building a society-wide movement of workers, and reifies the Marxist notion of false consciousness regarding class.

Occupy Wall Street, for all its flaws, had what I considered to be an extraordinary political culture. While its occupations of parks and mental health clinics and foreclosed homes embodied a radical, militant spirit by seeking out friction with the state and capital, its theory of society was one that was always inviting to those who might share values. Occupy pitched a pluralistic and communitarian big tent, radicalizing young people with inchoate beliefs and helping bring together radicals of all stripes with the kind of finance wonks who love Elizabeth Warren. While its anarchist organizational structure doomed its ability to endure, the open-heartedness of Occupy is a big part of why people still talk about a bunch of people camping in a park a decade later.

Those who advocate for unpleasantness should think carefully about how they are shaping broader perception of Sanders and his mainstream following — and undermining them. Sanders, cranky and gruff as he is, always seeks common ground with other people along class lines, and unequivocally condemns hurtful attacks and bullying. “Our campaign is building a multi-generational, multi-racial movement of love, compassion, and justice,” Sanders said after the attacks on the Culinary Union. “We can certainly disagree on issues, but we must do it in a respectful manner.”

The love stuff isn’t just an aesthetic, it’s political philosophy. In a movement-building context, it means patience, tolerance, optimism about the human spirit and channeling rage into something productive. If love is foundational in your political culture, then you tend to be more discerning about whom you consider a real enemy. Sanders’ rhetoric is more capacious than some of his followers, and they’d be wise to more closely follow his example.

Could demoralizing Sanders skeptics or scaring them into thinking you’ll throw the election work for securing the nomination? Perhaps. But its hard to see how doubling down on this culture won’t undermine the left’s sustainability and its soul in the long run.

This essay was featured in my politics newsletter, which you can sign up for here.